Recent developments in Syria have reignited deep fears among Ezidis (Yazidis) in Shingal, where memories of the 2014 genocide remain painfully alive. Over the past two weeks, changes in daily life—stockpiling food, purchasing tents, and even seeking weapons—reflect growing anxiety that history could repeat itself.

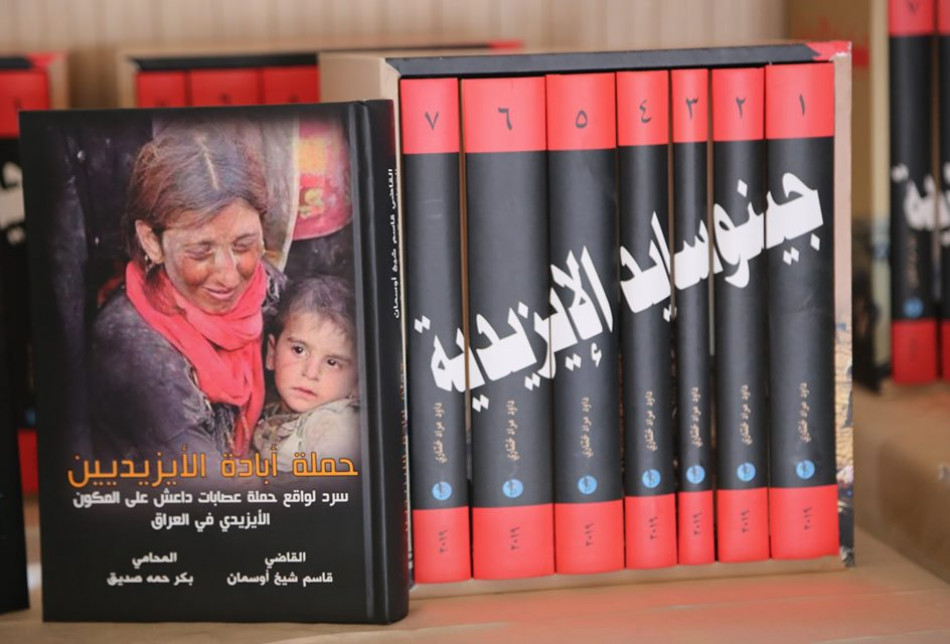

In 2014, the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) seized vast areas of northern Iraq and carried out systematic atrocities against ethnic and religious minorities, particularly Ezidis and Christians. In Shingal district of Nineveh province, Ezidis were subjected to mass killings, abductions, sexual violence, and forced displacement in what later came to be recognized as genocide.

Today, similar fears are being stirred by events across the Syrian border, including shifting control over detention facilities holding IS prisoners and discussions about transferring thousands of these detainees to Iraq.

The concern intensified after forces affiliated with the Syrian Arab Army, led by Ahmad Shara—previously associated with IS—expanded their control over areas formerly held by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). These areas border Shingal district and parts of the Nineveh Plain, the same routes through which IS infiltrated into Iraq in 2014.

People are preparing for another catastrophe. Some have bought tents and stored dry food

“When will this fear end?” asks Ibrahim Khadr, a resident of the Grozer area in Shingal. “People are preparing for another catastrophe. Some have bought tents and stored dry food.”

Shingal lies roughly 20 kilometers from the Syrian border. Many of its residents were displaced in 2014 and have yet to return to their homes. Although Iraqi Interior Minister Abdul Amir Al-Shammari visited the border on December 22 and assured residents that the frontier is fully secured, fear persists.

“The difference now is that we trust the border forces more,” one resident said. “But we are afraid of secret agreements and conspiracies. We fear something could happen suddenly.”

These concerns are compounded by the Iraqi government’s agreement to receive approximately 7,000 IS prisoners currently held by the SDF, including both Iraqi and foreign nationals. Sabah Al-Numan, spokesperson for the commander-in-chief of the Iraqi armed forces, confirmed that 150 prisoners have already been transferred as a first phase.

The move has sparked controversy. Ezidi lawmaker Murad Ismail described the decision as “dangerous,” warning that Iraq’s prisons lack capacity and that the transfer poses a threat to national security.

Fear levels vary across Shingal. “In some areas, people have hidden tents, food, and supplies in Mount Shingal and nearby caves,” said Saad Haji, an Ezidi civil activist. “This time, people say they will not hand over their land to anyone.”

In response to developments in Syria, Iraqi forces have increased troop deployments along the Syrian-Iraqi border, particularly in Nineveh province. Army units, local police, Pro-Shiite Popular Mobilization Forces PMF known as Hashd al-Shaabi forces, Shingal Resistance Units, close to Kurdistan Workers Party PKK, and Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) Peshmerga forces are all present in and around the district.

“Our forces are fully prepared to respond to any attempt to storm the area,” said Mirza Khalaf, a Peshmerga commander stationed near the Sharfaddin shrine, a prominent Ezidi religious site.

Despite official reassurances, local authorities acknowledge the underlying tension. “Daily life continues normally, but caution is necessary,” said Jalal Khalaf, a government official in Shingal. “The increase in food purchases reflects public anxiety.”

Our forces are fully prepared to respond to any attempt to storm the area

Mohammed Jassim, head of the security committee in the Nineveh Provincial Council, said that Ahmad Shara’s forces are unlikely to cross into Iraq unless internal instability occurs. He stressed that the borders remain protected and urged residents not to panic.

Ezidis in Iraq are concentrated mainly in Shingal and the Nineveh Plain. According to the KRG figures, Iraq’s Ezidi population stands at around 550,000. Since 2014, approximately 360,000 have been displaced, and more than 100,000 have migrated abroad.

The KRG’s Office for the Rescue of Ezidi Kidnapped Persons reports that only 3,580 of the 6,417 Ezidis abducted by IS have been rescued. At least 2,293 were killed, while the fate of thousands remains unknown.

Against this backdrop, fear among Ezidis is not merely speculative—it is rooted in lived experience, unresolved trauma, and ongoing regional instability.